On four powerful films from TIFF, including works starring Anne Hathaway, Anne Heche, Sally Hawkins, and Gemma Arterton.

An article highlighting three films at Sundance 2016.

An interview with Morgan Neville and Robert Gordon, who directed "Best of Enemies," the opening night film at AFI Docs 2015.

A piece on six documentaries from Sundance 2015, including "Call Me Lucky," "Sembene!," "Drunk Stoned Brilliant Dead," "The Amina Profile," "Finders Keepers," and "Cartel Land."

Lists from our critics and contributors on the best of 2014.

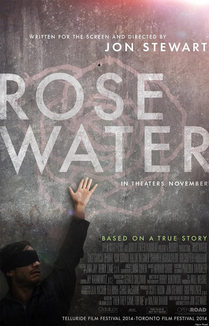

A report from the Telluride Film Festival on Jon Stewart's "Rosewater" and Nick Broomfield's "Tales of the Grim Sleeper."

The right kind of 90s nostalgia; Cynthia Rothrock: Expendabelle; Favorite Fincher moments; Ten underrated 2014 performances; Chatting with Whit Stillman.

Movies aren't math; Zac Efron's blank face fuels "Neighbors"; How critics should cover the increasing number of movies getting released; "House of Cards" vs. "Veep"; John Oliver's professorial satire.

The recent #CancelColbert campaign on Twitter raises all kinds of issues about racism, but also about hashtag activism.

The NSA plans to reopen the public vetting process for cybersecurity standards; "12 Years a Slave" and the dangers of early Oscar predictions; Disney's new app allows moviegoers to interact with movies while watching them (sigh); our computers are atrophying our brains; "Endless Love" author Scott Spencer on how his novel become a really bad movie (twice); the final moments of Winnie the Pooh; students demonstrate against random drug testing.

Writer-director-producer David Simon (creator of "The Wire," "Generation Kill," "Treme") has a piece at Salon headlined: "Media's sex obsession is dangerous, destructive," in which he eviscerates Roger Simon (no relation) for his Politico column, "Gen. David Petraeus is dumb, she's dumber." And The Week offers a round-up of trashy "journalistic" misbehavior, " The David Petraeus affair: Why the media's coverage is sexist." I don't know. "Sexist" seems like an understatement. Puerile, snotty, crass, raunchy, snide, scary, onanistic, stupid, instructive, pointless -- it's all those things, too. At the very least.

Rarely does a TV show arrive with lower expectations than the annual Emmy Awards telecast. It's a given that the thing will suck. Even so, this year's -- the 64th -- managed to come up short and disappoint. And it wasn't one of those "so bad it's good" campy things you can enjoy making fun of, either. It was more like one of those "so bad it's lousy" things that leave you incredulous and drained of the will to live.

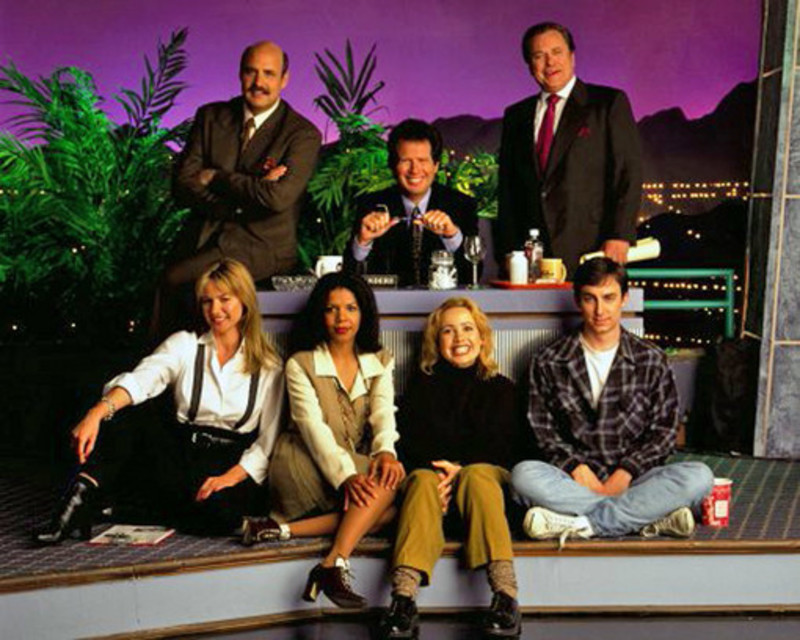

August, 2012, marks the 20th anniversary of the debut of "The Larry Sanders Show," episodes of which are available on Netflix Instant, Amazon Instant, iTunes, and DVD. This is the third and final part of Edward Copeland's extensive tribute to the show, including interviews with many of those involved in creating one of the best-loved comedies in television history. Part 1 (Ten Best Episodes) is here and Part 2 (The show behind the show) is here.

A related article about Bob Odenkirk and his characters, Stevie Grant and Saul Goodman (on "Breaking Bad"), is here.

by Edward Copeland

"It was an amazing experience," said Jeffrey Tambor. "I come from the theater and it was very, very much approached like theater. It was rehearsed and Garry took a long, long time in casting and putting that particular unit together." In a phone interview, Tambor talked about how Garry Shandling and his behind-the-scenes team selected the performers to play the characters, regulars and guest stars, on "The Larry Sanders Show" when it debuted 20 years ago. Shandling chose well throughout the series' run and -- from the veteran to the novice, the theater-trained acting teacher and character actor to the comedy troupe star in his most subtle role -- they all tend to feel the way Tambor does: "It changed my career. It changed my life."

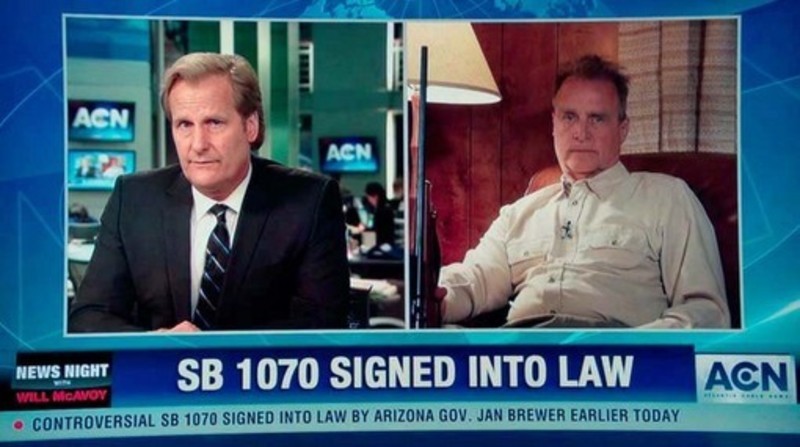

To best appreciate Aaron Sorkin's writing, you should probably know as little as possible about whatever it is he's writing about. Imagine that pithy, rather snarky statement delivered at a rapid clip from the mouth of one of Sorkin's characters. It's a generalization, an oversimplification, but it contains a kernel of truth. I'm gonna be rough on Sorkin's HBO show "The Newsroom" because, dang it, I think it can get better. (According to one character, getting better-ness is in our nation's DNA.)

The press has not been kind to the first couple episodes of "The Newsroom," in part because it displays so little affinity for how news is reported, written and presented. Anybody who's worked in a newsroom would have to cringe at the idea that these characters are being portrayed as professional newsgatherers, even if they are on cable TV, the lowest rung of the journalistic ladder -- just slightly below Murdoch tabloids which, at least, have reporters who gather news illegally rather than just making it up as they go along like they do on cable.

Having some familiarity with how "Saturday Night Live" is put together, I found Sorkin's "Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip" unwatchable, bypassing so many promising reality-based opportunities for comedy and drama while manufacturing absolutely bogus, nonsensical, unbelievable and impossible ones. Doesn't the guy do research? "The Newsroom" feels like it was written in Sorkin's spare time, perhaps between projects he actually cared about.

Don't get me started on his lack of technological savvy. When someone in a Sorkin script says something as common as "blog" or "Twitter" they sound like they're speaking Estonian. Because they may as well be. Even "The Social Network" was weak on showing how technology made Facebook into a popular and compelling user experience. As Bobby Finger at BlackBook wrote, MacKenzie McHale (Emily Mortimer) calls the rebooted show they're doing "NewsNight 2.0" because "in this parallel-universe-alternate-history-2010, people still speak like it's 2006. They also use email like it's 2001..." (More about that in a moment.)

On Netflix and Amazon Instant.

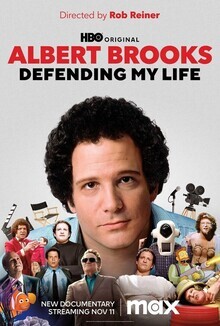

Considering that we normally think of documentaries as some sort of academic discourse at the fringes of popular cinema, this relatively new genre of Celebrity-driven docs is something peculiar. That we now watch documentaries starring Michael Moore, Morgan Spurlock, and Bill Maher is something inevitable, I suppose. We already have that tradition of following on-screen directors as characters in their features, including Kevin Smith, Spike Lee, and Woody Allen. But, the point here is that we watch some documentaries because of their host celebrities, more than the topic, even though the topics seem to be extensions of those same celebrities.

I suspect few people outside of his fan base will watch this movie: in Larry Charles' documentary "Religulous," (2008) popular Television talk show host Bill Maher is a playful microphone-toting cynic, roaming the landscapes of Christianity, with a few references to Judaism, Islam, and Scientology. The film is very strong and vastly entertaining in finding absurdities in absurd places, but fizzles when it attempts any serious commentary.

Rush Limbaugh's so-called "slutgate" brouhaha reminds me of a scene in Kenneth Lonergan's great film "Margaret." After a heated classroom argument about 9/11, a student says: "I think this whole class should apologize to Angie because all she did was express her opinion about what her relatives in Syria think about the fact that we bombed the shit out of a practically medieval culture... and everybody started screaming at her like she was defending the Ku Klux Klan!" Whereupon, one of the teachers says that jumping down someone's throat when you disagree with them is "censorship." Lisa Cohen (Anna Paquin) goes ballistic: "This class is not the government!"

Lisa's point is significant -- and it's one of the movie's many sharp insights into how Americans argue. We have a hard time separating our personal feelings from the legal system, a conflict that's goes to the core of Lisa's moral dilemma. (And for some reason we think it's a rational defense to say that someone else did something just as bad but didn't get punished for it as much.) The classroom of teenagers, reacting spontaneously and having a free discussion (even if it became raucous and uncivil) was not an attempt to prevent, modify or control the expression of Angie's ideas, but an attempt (by some, at least) to refute them. And while censorship isn't limited to government, church, commercial or social repression, the phrase "freedom of speech" (as outlined in the First Amendment) applies to government restrictions on what "the people" can say.

"Now, getting over 200,000 people to come to a liberal rally is a great achievement, and gave me hope. And what I really loved about it was that it was twice the size of the Glenn Beck crowd on the Mall in August. Although it weighed the same." -- Bill Maher, "Real Time," 11/06/10

Jon Stewart and Stephen Colbert's Rally to Restore Sanity and/or Fear was all about tone. As Stewart said in his speech, "I can't control what people think this was. I can only tell you my intentions." And that boiled down to this: "We can have animus and not be enemies." Stewart and Colbert are masters of tone, and I have often argued that Bill Maher is not only tone deaf in his delivery (some find it funny; I find it sanctimonious and condescending), but too often plays fast and loose with facts and logic. And yet, he provided an important perspective about false equivalencies in his remarks about the rally on "Real Time" this week, which he summarized like this:

With all due respect to my friends Jon and Stephen, it seems to me that if you truly wanted to come down on the side of restoring sanity and reason, you'd side with the sane and the reasonable, and not try to pretend that the insanity is equally distributed in both parties.

Keith Olbermann is right, when he says he's not the equivalent of Glenn Beck. One reports facts, the other one is very close to playing with his poop.

@jeeemerson god. Pretty soon we won't be able to tell a knock knock joke, for fear of hurting a doors feelings. STFU

That's an offended tweeter's response to my previous post, "The "gay" Dilemma: If it's a joke, what does it mean?" -- except that it's not really a response, exactly, since it doesn't address anything I actually, you know, said.¹ It's a tweet. Still, it expresses a fairly common attitude among those who are easily offended that others take offense to things they are not offended by: Why are people hurting my feelings by getting their feelings hurt over what I say or what I like? So, to those whose feelings have been bruised in this way, I want to say: Don't stop whining. Don't stop making it all about you. Keep on complaining that your sensibilities are being hurt because you feel that other people should not express opinions other than your own. How dare other people claim that things you honestly feel are funny are not only not funny to them, but maybe even painful or insulting!?! What if that's not even what you meant at all? Just remember, when your feelings are hurt by somebody who says you've hurt their feelings, it's all their fault for being so sensitive to what words mean and being so rude as to tell you. Blame them. You shouldn't have to accept responsibility for what you do or say or laugh at. That's just not fair!

But seriously, folks...

Several of yesterday's commenters mentioned comedic treatments of the anti-gay epithets "fag" and "faggot" on "South Park" ("The F Word") and Louis CK's series, "Louie," which is where the clip above comes from. A group of comedians are discussing the implications of using the word "faggot" in Louis's stage act. Louis asks Rick, the only gay comic at the table, if he thinks he shouldn't use the word. Rick says, "I think you should use whatever word you want... but are you interested to know what it might mean to gay men?"²