Of late, I've been thinking about how I got here. Here, in love with movie watching and movie making. Here, in a design school in India, and not an engineering college or a medical school like predetermined for most Indian students. Here, in correspondence with a huge role model of mine. Here, doing what I love.

I guess it's all thanks to a beautiful series of events and coincidences. Even today, as I think back, I'm discovering little things that made big changes. How the purchase of a random toy led to something big. Or how the viewing of some documentary on TV led to a page on the internet that led to something else entirely. If any one of those little things didn't happen, I wouldn't be here. If there are indeed parallel worlds with other versions of me leading different lives, I'm almost certain I've got the best deal.

Who I am now and where I am now also has a lot of it has to do with what I was exposed to as a child. My father spared no expense in surrounding me with whatever I wanted, whether I needed it or not. Toy cars, Ladybird Children's Books, action figures, et al. It's a wonder I wasn't a spoiled child. When I grew up a little more, it was VHSs (DVDs weren't around yet). My mother and father bought me numerous Disney classics.

And soon, my mother introduced me to the greatest movies I have ever seen.

She brought to me "Superman," (1976) "Close Encounters of the Third Kind," "E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial," "Back to the Future," "Raiders of the Lost Ark," "Who Framed Roger Rabbit," and several others. As I grow older (I am now eighteen), I chance upon more serious films, films that are deemed "classics," films that end up on those lists of the greatest films of all time et al. While I find some of those films remarkable, and some curiously engaging, I still prefer my "Back to the Future."

It is my good fortune that my mother showed me just the right films at just the right age. I'm not sure if she knew she was doing it, but she was feeding my growing imagination and love for film to such an extent that I began looking at the world through the lens of a camera, in my mind's eye. As I perceived objects around me, I quietly looked at them from mental camera angles. (I was just eight or nine when I got into this habit; I didn't know they were called camera angles.) Now that I think of it, my childhood was sort of the opposite of The Truman Show. In the show, everyone knew Truman's life was on TV while he did not. In The Krishna Show, I was the only one in on the little secret. The rest of the world was unaware. Yes, I was a silly child.

But even though I was, and maybe still am, a silly child, I'm grateful that I grew up surrounded by Spielberg's magic, Christopher Reeve's Superman, Disney's early live action comedies, their animated classics, and Ray Harryhausen's visual wonders, while most kids my age grew up with the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, the Power Rangers, and whatever was playing on cable TV. I'm thankful I went through junior school with my imagination ignited by what I believed to be magic, and not blown to bits by explosion-happy TV shows and kiddy kitsch. I'm sorry if I've watered down your childhood memories by my analogies and what may be mistaken to be condescension. I might be wrong. I beg your pardon.

Anyway, my mother saw all those wonderful films with her eldest brother, who would read print film reviews to decide whether buying two tickets for that particular film was a worthy investment. If it was well reviewed, to my mother's delight, they would go to the movies. You can see her smile with her eyes when she talks about all this, and most times that smile's contagious to me.

She still fondly remembers how she fell head over heels for Christopher Reeve's Superman. And later, Harrison Ford's Indiana Jones. And then, Michael J. Fox's Marty McFly! Her love for these films was hardly fueled by her crushes on these movie icons, though. It was the magic that got to her, and many years later, me. These films had extraordinarily memorable imagery, and more importantly, great stories and characters that you loved and cared for. Some created new worlds, other filled our own world with the fantastic. These movies felt inviting and friendly, and though they sometimes had the most absurd and out-of-this-world ideas, you felt like you were watching... I dunno, close friends? It feels like that to me, at least.

Once we bought ourselves a DVD player, my mother began a habit of taking me shopping with her and buying me the DVD titles that were on discount. I thank my stars that many of Spielberg's great movies and most of the Ray Harryhausen Signature Collection were among those titles.

So, like I said, whatever I saw as a child deeply influenced me and sent my mind reeling with ideas. And the effect these movies had on me grew deeper and more profound--it brought me to think about the most crazy things, and later to the realization of these ideas. Experiencing those wonderful stories, I felt a great urge to tell my own. I started with comics. Now that I think back, I remember several of the images from my Superman comics, of which I made oh-so-many! I also remember I was so young when I came up with them that I couldn't even draw a proper Superman logo. Back then, a triangle with an 'S' scribbled in it seemed adequate.

My Superman dealt with his issues in interestingly odd ways. Consider this classic Superman obstacle; a giant asteroid is heading straight for Earth. The original Superman would fly straight for it and the collision would destroy the asteroid. My Superman had the mind of a seven-year-old. What does he do? He 'laser-beam's the Earth in half, letting the asteroid pass right through the center. And then he fixes the Earth back together again. Obviously.

After comic book creation, film making came next. I unearthed a rarely used Sony Handycam. (This was back in the days of cassette tape recording, so the editing and special effects were all done in camera, while shooting.)

Enter Ray Harryhausen, who I discovered myself by accident. In many ways, he changed my life. Harryhausen has told us, time and again, the story of how he saw the original "King Kong" on the big screen when he was just a kid, of how he was inspired by Willis O' Brien's pioneering special effects and of how that lead him to where he is today. In case I end up in the movies, I foresee myself telling people the story of how I was inspired by Harryhausen's work. Hopefully, the chain will go on. I am kidding, of course, but it's a nice thought anyway.

While most kids in the 90's would be oblivious of stop-motion (with CGI growing popular), I was in awe of it. There is a sense of life in stop-motion animated creatures. It's the kind of life that much of CGI lacks. No matter how smoothly or realistically your computerized monster moves, there is something more subtle that stop-motion captures better. Harryhausen's creations seem to be thinking, or feeling, not just moving. They have personality, an attribute that so many of today's CG monsters lack.

Also, no matter how crude a stop motion model might be, it still exists. It occupies space and has weight. The Transformers, no matter how many cars they bump into and send flying, aren't really there, and many times, they seem to be walking 'through' space, not occupying it.

One more thing that gives stop motion animation a distinction from other forms of animation is the dream like quality it has. While 2005's CGI "King Kong" was a wonderful work of modern CGI special effects, the 1933 film has a nightmare quality to it that CGI will never achieve. Look at the realistic Pegasus from the recent remake of "Clash of the Titans" and then look at Harryhausen's version? Tell me, which one left you smiling?

There is a spectacular sequence in Harryhausen's most popular picture "Jason and the Argonauts" in which Jason and his crew do battle with seven sword fighting skeletons. This is surely one of the greatest special effects sequences in motion picture history. There are shots in which the screen is filled with the men fighting all seven skeletons. This means that Harryhausen would have to move each of the seven skeletons such that they match the chaotic live action footage of the men mock-fighting, shoot a frame, move them again one by one, shoot a frame, and so on. 24 frames make one second of action. It is hard to imagine how Harryhausen did all the special effects on his films solo (save for his first and last films, on which he had help). And it is not surprising that the skeleton sequence from "Jason" took him four months to complete.

Other films of his have very challenging special effects too. If you have not watched any of his films, YouTube them and watch the brilliant sequences. That'll convince you. Try the sequence where the cowboys try to "rope" Gwangi, in which Harryhausen had to painstakingly match the ropes on the live action footage to the ropes on his stop-motion model. Or the tug of war in "Mighty Joe Young," using a similar technique. Or the sequence with the giant bird from "Mysterious Island," which works well with Bernard Herrmann's goofy score. Or the Washington destruction scenes in "Earth vs. Flying Saucers." Or It from "It Came From Beneath the Seas." Or Pegasus in "Clash of the Titans," or Medusa, from the same film. Or anything from "The Seventh Voyage of Sinbad," my personal favorite film of his.

Ray Harryhausen's career is a long one, populated by dreams and nightmares, masterfully shot one frame at a time.

You can see Harryhausen's influence on so much of today's fantasy film world, from the work of Spielberg (there are references in "Jurassic Park") to the films of Tim Burton (he is one of the strongest supporters of stop-motion today. The piano in "Corpse Bride" has a name plate that reads "Harryhausen) to Peter Jackson (who remade Willis O'Brien's "King Kong" into one of the greatest fantasy adventures in recent years) to even Pixar (the restaurant in "Monster's Inc." is called "Harryhausen's").

In an attempt to recapture some of the magic that amazed me, I tried stop motion myself. I had a very basic idea of what stop motion was from a few documentaries I saw among the bonus features of the DVDs my mother bought me, but no one ever taught me anything or asked me to do it. I was my own student and teacher, and it was my own interest that fueled my persistence. All I had was a camera that recorded on tape. How did I shoot the video, frame by frame? I would quickly double-click the "record" button, hoping that the little shots I was getting were all around the same length, and short enough. They really weren't, but back then, it worked for me.

Harryhausen deserved better films and higher budgets (his films were so low budget that at several times, the full extent of his vision wasn't realized. It is now popular trivia that the octopus in "It Came From Beneath the Sea" actually had only six tentacles as they couldn't afford to build a model with eight). Though the films have inspired several of us, it was, in most cases, only the special effects that kept the films from being mediocre B-movie fare. It is sad that he didn't work with greater talents. Imagine what would have come out of such collaborations.

This master of animation was snubbed by the Academy year after year for each of his films, the films not even getting nominations for their special effects, until, years after his retirement; they gave him an honorary Oscar, which, I suspect, is more of an apology than a token recognition. I've read somewhere that Harryhausen reasons his films didn't get recognized by the Academy when they were released because they were shot in Spain, and not in Hollywood. It makes sense.

Once my fascination with special effects faded, I was interested in another aspect of fantasy films. Story. And this is where Steven Spielberg comes in. His films (at least the ones I watched then) all had to do with the fantastic, and all their stories were extremely well told. Most of the films of his I saw then dealt with this incredible synergy of amazing fantasy and honest humanness. Boy, is that a mouthful.

My mother tells me of how she, as a child, would lay down on the terrace under the night sky and search the heavens for shooting stars, all because of "Close Encounters of the Third Kind." How many films produced today inspire that sense of wonder in children? Few film producers stop to think about these things while they're too busy calculating the box office numbers and sequel prospects.

I consider "Close Encounters" to be Spielberg's greatest achievement, and that's saying something, considering the number of revolutionary films he has given us. You can call him "syrupy" or "sentimental," but no one can deny the fact that he changed things and brought us some great stuff.

"Close Encounters" follows Richard Dreyfuss's character Roy Neary as he, after experiencing "close encounters" with UFOs, becomes increasingly obsessed with the mystery of the aliens. He wants to know what those lights in the night sky are and why there are seemingly meaningless images of mountains in his head. His obsession grows to a point where he is completely disconnected from his family.

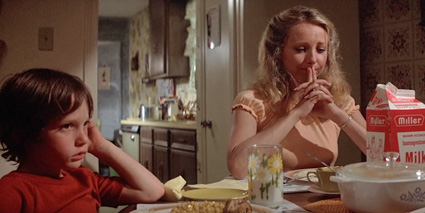

There is a very well acted-out scene in the film, around halfway through it, at the dinner table. Roy is playing with his food, forming mountains out of the contents of his plate, lost again in thoughts about the images in his head. He notices his family staring at him and stops. His eyes move between his three confused children and his wife, who is suppressing tears. His son looks at him, tears falling from his eyes, as Roy covers his face, holding back tears too, and says, "Well I guessed you've noticed something's a little strange with dad. But it's okay." He looks up at them. "I'm still dad."

"I can't describe it. What I'm feeling. What I'm thinking. This means something. This is important."

His wife looks at him, convinced he is a lost cause. She has lost the man she fell in love with. But then again, judging by the scenes that take place before these "close encounters" begin, she, in some ways, lost him a long time ago. There is no more love in the family.

In the dinner table scene, we see that Roy's wife doesn't understand him, he doesn't understand his family, and the poor children don't understand what their father is turning into. Later in the movie, when Roy seems to go further round the bend, hysterically trying to make a larger model of the mountain using everything from dirt in the garden to the neighbor's fence, his wife takes the kids and leaves. He tries to stop them at the moment, but once they're gone, he continues making the model. At a point, he seems to forget about his family.

Consider the end of the film. As Roy walks into the mother ship, he looks back at Jillian (a woman who has had a similar close encounter to his) and smiles. Does he think about his wife then? And what of his children? He is leaving them for the unknown. He doesn't know if and when he will be back.

Spielberg has said that if he had had children back when he made "Close Encounters," he would never have let Roy leave his family. It's a good thing that things worked out the way they did. I believe "Close Encounters" would have been a lesser film if Spielberg did it today with his present sensibilities.

Of course, the emotional complexity of the film was lost on me then, but that didn't make the film any less amazing. The visuals were enough.

Designed by Douglas Trumbull, of "2001," they are breathtaking and so original, and to this day, I have not seen a more beautiful spaceship at the movies. Spielberg has always worked with glowing lights in very interesting ways, be it the sun, a gigantic moon or flashlights, but here, the lights drive the film, whether on or off the screen, and many a time they make us stare at the screen, gaping, much like the characters in the film.

Though most people, including Spielberg, would remember the image of the boy opening the door to the golden light outside, the first image that comes to mind when I think of the movie is the shot of the boy and his mother crouched on the road, when the first UFO of the film is seen, flying into the shot from around the corner. There is a low hum as it flies by, giving off a wonderful ochre glow. And then it is followed by a few more.

"Ice-cream!" the boy shouts after one of the UFOs that fly by. Indeed, there is one that looks oddly like an ice-cream. Later in the film, I noticed a UFO that looked conspicuously like an oxygen mask, but I did not expect anyone to shout that out.

The third act of the film, at Devil's Tower (the mountain images that Roy has in his head are actually pointers to the location of the place where first contact is to take place), is exceptionally memorable. It is an excellent sound and light show, with its strong memorable visuals aided by John Williams's excellent score. Spielberg supposedly edited that section of the film to match the music, instead of the usual method of composing music to fit the edited film footage. (Now that I think of it, it can be said that John Williams scored most of the music that I played in my head as a child. This man is responsible for most of the great movie themes. "Jaws," "Star Wars," "Indiana Jones," "E.T.," "Superman," "Close Encounters," "Jurassic Park," "Harry Potter." All one man. Wow.)

The third act reinforced my belief that instrumental music was a sort of universal language. "Lyrics are irrelevant; instrumental music can capture emotion perfectly well on its own," I used to say, defending my choice of music, which consisted of only movie scores. But think about it: what is the five-tone anyway? What could it mean? The aliens play it to us and we back to them, without knowing what it means. And yet we all have this strange conversation. And it goes well, which is vital. Remember first contact in "Mars Attacks!"?

Roy, who was an outsider in his own home, separated from his family, feels right with the aliens. "We Are Not Alone," reads the tag-line of the "Close Encounters." It makes sense on more than one level.

Few films have impressed me as much as "Close Encounters," and even fewer will stick around with me the way I know this one will. I often say I would like "Close Encounters" to be the last movie I watch before I die. Though I say it as a joke, I will not deny there is some truth to those words.

But I doubt "Close Encounters" was my introduction to Spielberg. I think I saw "Jaws" first. Yes, I definitely did. The film got me obsessed with sharks. I began to collect books about them, read about them, and draw them everywhere I could. Thinking about those drawings now, I realize that I drew most of my sharks posed in the manner of the Great White on that famous "Jaws" poster. The film had such an effect on me that, apart from studying sharks in startling detail, for a kid my age anyway, I stuck to the shallow side of the swimming pool in our building for a while. (Now that I think of it, it might be questionable behavior to let your kids watch "Jaws." Though I am thankful that she showed me all those movies when I was young, my mother also exposed me to stuff like "The Exorcist" when I wasn't ready for it yet. I was, what, nine? Eight?)

Watching "Jaws" recently, I was amazed by how effective it is. It absolutely terrifying because it doesn't show you what is killing these people for an unusually long time. There is something horrifically scary in not knowing, and Spielberg is daring in not how he shows us the shark, but how he does not. I now realize that it is a great compliment to Spielberg and his team that I recall there being more scenes with the shark than there actually were. It just goes to show that though the shark is hardly in the shot, its presence is felt so strongly in the scene. Spielberg masterfully builds up the tension for the first two acts of the film. The third act is when all hell breaks loose and the shark shows itself. Though those shark scenes may look a little tacky when seen in isolation, the obvious fakeness of the shark does not in any way reduce the strong impact of the film when seen in it is seen in its entirety. It's all in the buildup.

And it helps that the three protagonists all play their parts excellently. The scene at night, in the boat's cabin, is a perfect example of how Roy Schneider, Richard Dreyfuss and Robert Shaw portray distinct characters that contrast well with each other: the straightforward police chief, who is afraid of water; the young, passionate marine scientist who comes from money and seems to want to prove himself; and the fisherman, who doesn't give a shit about you. He wants to get that shark. He has his reasons.

In that cabin scene, the three separate characters seem to compromise on their differences. They know they need to work together to get that beast. That beast, who has been terrorizing their little town and killing their people. And ruining their summer tourist season, the mayor might like to add.

There are daring shots in Jaws, some excellent underwater POV shots that help build up the tension, and some very interesting transitions (consider the scene in which Brody is on the beach with his wife, looking at people playing in the water, fearful of a shark attack. Each shot flows into another with a person on the beach walking past the camera), and John Williams's Oscar winning score adds to the film greatly. Though it is one of Spielberg's earliest films, it is also one of his greatest. Many say that no film of his since has reached its greatness. That film and the excellent "Duel," which I saw much later, are films with simple story lines that yet keep us on the edge of our seats, or tucked hard in them.

"Jaws" became the highest grossing picture made at the time (1975). In 1982, Spielberg gave us "E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial," which, again, became the highest grossing film at that point. (Spielberg would break his own record again, with "Jurassic Park," a film I have somehow never admired as much as the rest of the world.)

"E.T." is surely his most popular effort. Spielberg himself has said that it epitomizes his work. It is one of those rare films that feel both powerful, uplifting and big, and sweet and gentle at the same time.

"E.T," as most of the world must know, tells the story of the friendship between a boy, Elliott, and an extra-terrestrial being lost on earth. The extra-terrestrial, called "E.T.," is a masterwork of movie creature design by Carlo Rambaldi, who also created the alien creatures of "Close Encounters." Spielberg employed animatronics, puppets, and dwarfs to realize this iconic character, and it is surprising how well he pulls it off. The little creature was voiced by Pat Welsh, a woman that legendary sound designer Ben Burtt ("Star Wars," "WALL-E") chanced upon in a camera store. Imagine, the source of that endearing voice saying "E.T. Phone Home," is actually a chain-smoker. Whatever works, right?

Apart from the great technical skill involved, "E.T." was so successful because of the great, natural performances by its child actors. In fact, the film is populated with them. For the first two acts of the film, all adults save for Eliot's mother Mary (played wonderfully by Dee Wallace) are shown from the waist down, much like in the "Tom & Jerry" cartoons we all grew up with. Somehow, us kids, we weren't bothered by that one bit, were we?

Henry Thomas is excellent as Elliott (notice how the first and last letters of Elliott are E and T?). There are several scenes that a lesser child actor could have messed up, but Thomas plays the character the way a real child would react. There are scenes that require him to cry, and laugh, and be amazed, and so much more, and he pulls it off beautifully. His performance is part of the reason the film touched so many of us in ways not other movie has. I wonder what he is doing today.

A young Drew Barrymore plays Elliott's sister Gertie. She is touchingly sweet, hilarious, curious, and so natural, but if I were to find my own E.T. and Gertie was my sister, I would not tell her. It's too dangerous; more than once in the film does she endeavor to tell her mother that her son is hiding an alien in his cupboard.

One more thing to appreciate about "E.T." is that, though it is clearly a children's film, it never talks down to kids. It does not assume that they will not understand some aspects of it.

Consider the theme about Elliott's father. Where is he, through all of this? There is a scene early on in the film, when Elliott tries to tell Mary, his elder brother Michael, and Gertie that he saw something strange in the shed. They dismiss it, saying it was his imagination. "Or a leprechaun. Or alligators in the sewers," Michael adds, helpfully. Elliott says that no one will believe him. His mother suggests he call his father and talk to him about it.

"I can't. He's in Mexico with Sally," says Elliott, at the table. There is a long silence. Mary is clearly hurt, trying to fake a smile, while Michael gives Elliott an accusing stare and looks like he knows he has to say something, being the elder.

And then a confused Gertie softly speaks. "Where's Mexico? Who is Sally?"

Scenes like this are honest. They are not cute. They are real. They do not water anything down for children.

When E.T. drops in, he is there for Elliott in a way no friend, brother or father has been. And in a strange new world, Elliott is the only person E.T. can trust. There is a beauty in their relationship, in how they both need it. It isn't about a boy helping an alien, like one would be quick to say- they are helping each other.

There are two scenes in "E.T." that I particularly admire. The first is an obvious choice and the second is less so. The first is the beautiful sequence when Elliott is riding his bicycle through the forest with E.T. up front. "It's too bumpy. We'll have to walk from here," Elliott says. E.T. telekinetically controls the bicycle and sends it forward as Elliott screams. They're heading toward a huge drop. And we all know what happens then. That sequence is among the most memorable in film history. The shot of the two of them flying on the bicycle silhouetted against the huge beautiful moon is iconic.

The second scene is the one in which Elliott first introduces E.T. to Michael. You know, the one in which when Gertie walks in. That sequence is well shot, well edited, and, primarily, well acted. She takes one look at E.T. and stops in her tracks. E.T., in shock, extends his neck. Gertie screams. E.T. screams. Michael backs up into a wall and knocks some shelves off the wall. Elliott screams. We laugh.

I saw the film for the first time when it was re-released in 2002, on the big screen. I was nine, and amazed. My sister's friend watched it with us. She must have been seven or eight. I remember how we had all cried at some point, and how we were all amazed at what we had seen. Later, I got to know that my sister's friend was under the impression that the alien was real. If you ask her about it now, she might deny it, but I remember.

Thinking more about "E.T.," I suddenly remember how wonderfully Spielberg incorporates popular fairy tales into his own tales. In "Close Encounters," there are references to "Pinocchio," in dialogue and in music (John Williams does a variation of "When You Wish Upon a Star" near the end of the film). Roy Neary wants people to believe him. He doesn't want to look like a liar. He wants to show everyone that he did indeed see flying lights in the sky. He wants the lights, the aliens, to make him a real boy, to show him what he doesn't know. Now, suddenly, I am reminded of Spielberg's "Artificial Intelligence," one of his best more recent films.

And what of the fairytale in "E.T."? There is a delicate scene in which Mary reads "Peter Pan" to Gertie as E.T. watches quietly from the cupboard. I suppose E.T.'s adventures on Earth are much like Wendy's on Neverland. She enjoys the adventures for the most part, and she loves Peter but she needs to go back home to her kind. But Peter wants her to stay. "You could be happy here, I could take care of you. I wouldn't let anybody hurt you. We could grow up together, E.T.," Elliott says. Of course, Peter Pan's idea wasn't to grow up.

But what if he did grow up? Spielberg attempted to answer that question with his "Hook" in 1991. Critics hated the film, and today it is remembered as one of Spielberg's worst offerings, but, having had recently seen it, I don't see what is so bad about it. It worked for me, and often made me smile. But "Hook" is a topic for another day.

More important is Indiana Jones.

I am in love with the original film trilogy, and yes, I quite like the new addition, though not as much as the classics.

There is so much to admire and enjoy about the Indy films. The films take you on incredible adventures in all kinds of exotic places, and they make you cover your eyes and smile and scream and just sit back and chuckle at (or with) the characters and all that is happening on the screen.

They have brilliant heroes that don't seem cardboard, despite there not being as much character development as you'd expect from Spielberg. Again, that's not a criticism, but an observation. It's not a shortcoming of the series, but Spielberg's attempt to capture the feeling of those old TV serials. And it's not like the film doesn't have enough in it for it to require character development. The film is above that sort of thing.

I enjoy Harrison Ford's Indiana Jones. I think he's the only one who can do it, and if you know your history, you'll know it's just one of those lucky happenings that he got the role in the first place. He plays the role with a sense of serious kidding, if you get my meaning. No matter how many times he's back-stabbed, beaten up, raced, cheated, whipped, chased, poisoned or shot at by Frenchmen, Nazis, Kali worshippers, or whoever else Spielberg's ready to make into a heinous villain we'd love to hate, Indy is ready with that droll smile, his sidekicks, and his whip. And his fedora. Never forget the fedora.

Speaking of sidekicks, the Indy girls add to the whole thing too, so much so that I think calling them 'Indy girls' belittles their forceful natures. Bond girls are, more often than not, just Bond girls. Spielberg never objectifies Indiana Jones's girls. Indy playfully objectifying them is another matter.

When I was younger, I always favored the gorgeous Willie, played by Kate Capshaw, because, well, she was gorgeous. Now, I think she screams too much and is more often a liability to Indy than an aid, but I enjoy her character nonetheless. I don't understand the hate from fans. Of course, age has brought with it the understanding of a simple truth: Capshaw's character has nothing on Karen Allen's Marion Ravenwood, who is so spunky she's never watching from the sidelines; she participates. Perhaps I like the fourth film more than I should because they brought her back. It felt like a wonderful reunion of old friends, if nothing else.

I smile when I think of Indy and his dad, played by Sean Connery, and all that they did together in "The Last Crusade," the funniest of the Indy films. The relationship between them is well developed (being, perhaps, the strongest relationship in the Indy films). They both need to prove themselves to each other on different levels. Dr Jones needs to prove to his son that he did and does indeed care for him, and Indy needs to prove to his father that he is worth something. "Don't call me Junior," he says, more than once. It seems to be a running joke in the film, but there is some deeper meaning to it that slowly reveals itself as the film proceeds.

The conclusion of "The Last Crusade" is quite beautiful, regarding the father-son story. It does not end in a massive spectacle of special effects or a pulse quickening action scene like the rest of the movies, but in a quieter, more human way.

It is quite a feat, now that I think of it, that these action films have such memorable characters. Again, I compare those films to the ones that pop up today: how many mainstream action films bring us to care for the characters?

Coming back to Indy. I really, really enjoy the special effects throughout the series. The mine cart chase in "The Temple of Doom" is spectacular, and few action chases sequences can match up to it. I learned that whole sequence was done using everything from sets, blue screens, matte paintings, models, to stop-motion animation. Ben Burtt recorded a roller coaster's sounds for the scene.

That whole sequence of the opening of the Ark of the Covenant in "Raiders" is brilliantly ethereal, and I do not know what the heck you're talking about when you call them fake-looking cheesy effects. The melting faces send me smiling with delight.

One of the key reasons for the success of the action sequences in the "Indy" films, I think, is that they are well directed, well edited, inventive, and fun to watch. You know where the characters are in relation to each other and have an understanding of what's going on throughout. Most films today, even Christopher Nolan's great Batman movies, have failed at achieving that level of engagement with their action scenes, thanks to choppy editing, shaky cameras, and the filmmakers reliance on the "It's like that because we're going for realism" excuse. There is a balance between putting you in the shoes of the action hero and letting you in on exactly what he is doing, and Spielberg is the master of that balance. Even in his new "The Adventures of Tintin," with its kinetic, over-the-top action scenes, one even being a five minute long single shot, he lets you know what's going on.

Only recently, I learned that "The Temple of Doom" was banned here in India. The powers that were didn't let Spielberg and his team to shoot in India and rejected the script, saying it was too offensive to Indian culture and Hinduism. The government demanded several changes to the script and final cut privilege. Obviously Spielberg would not have it. He shot the film in neighboring country Sri Lanka, doubling for India, and it's all just as well. I am an Indian, and I was born a Hindu, and yet I don't see what is so wrong with the film. Even today, you will not find a DVD of "Temple" here in India. Not an original copy, anyway. You need to know where to go.

Bottom line, the Indiana Jones film are great fun, and they know it. I hold it in higher esteem than the Star Wars trilogy, simply because I was more engaged in Indy's adventures. Now surely most of you have no respect for my opinion.

When I was younger, there was another film trilogy that impacted me much more than "Indiana Jones": the Spielberg-produced, Robert Zemeckis-directed "Back to the Future" trilogy.

The "Back to the Future" films are sensational entertainment, because of the rich, clever stories, the well fleshed out characters, the awesome visuals, the fun feeling to the whole thing, and so much more. There is endless innovation within the plots of the films, particularly the first one. The next two feel like unnecessary extensions, now that I look back. Zemeckis didn't even want to do them, but others pushed for it, or so I've heard it said.

The first film is a masterpiece. The story is brilliant, original, well told, and something you can relate with. The questions asked, "What if you went back in time and saw your parents when they were your age?," or "What if your mother had the hots for you?" surely get you asking yourself those questions. You might shudder at the answers, but more often than not, you'll catch yourself laughing at Marty when he goes through the answers, after being sent thirty years back in time to 1955. The film has scenes of genius, like the one in which Marty is sitting in the café, unaware his father is seated next to him. They both are in the same pose. "McFly," Biff, the film's bully, calls from behind, and they both turn the same way. Like father, like son, you think. Later in the movie, we realize how far from the truth that is.

Michael J. Fox is very good as Marty McFly, with his amazed, confused face never failing to humor us. The initial scenes of him in 1955 work very well, with him walking around, flabbergasted at how everything is (or was) different.

And then it happens: Marty accidentally stops his parents from meeting the way they should have. And so Marty's mother, Lorraine, played by the beautiful Lea Thompson is smitten by Marty instead of the man she is supposed to marry, putting Marty's existence in danger. There are a couple of hilarious and awkward scenes in which Lorraine tries to get close to Marty, even trying to kiss him at one point. The look on Michael J. Fox's face during these scenes is priceless. Soon, he realizes the only way to save his own life and restore everything to the way it was supposed be is to get his parents to fall in love. And so he starts pushing his father George McFly, a shy, awkward, teenage sci-fi geek, to ask Lorraine to the upcoming dance. George is played by Crispin Glover, who is hilarious and so convincing in the role. In a film so funny, it is a great compliment to him that I find him to be its funniest aspect. I wish he returned to do the next two movies instead of asking for more dough and therefore being written out.

Oh, and Thomas Wilson is just brilliant and, I think, quite underrated as Biff Tannen, and his ancestors and descendants, throughout the series. "Hey, butthead. Why don't you make like a tree... and get out of here?" Man, you can never forget these movies!

I have done the impossible. I've written some three hundred words about "Back to the Future" without mentioning Doc. Christopher Lloyd is crazily, hilariously superb as Dr Emmett L. Brown, the creator of the DeLorean time machine. Boy oh boy, did I love that character. I even named my cat "Einstein," after Doc's dog. When I was that age, the German scientist was secondary to Doc Brown's dog.

The friendship between Marty and Doc keeps the films running. I know I might be repeating these phrases, but damn, does it feel me with glee when I think of all the "Great Scott!"s and "This is heavy!"s the two characters have shared! Their relationship is the only aspect of the series that keeps getting better throughout the series. You really do care for these two people, and all the crazy situations they find themselves in.

Part II was a loud film that was less easy to relate to, but Marty and Doc keep it afloat, as does the ingenious third act (which has them go back to the 1955 events of the first film). I enjoyed the little jokes in the 2015 section of the film, like the Hoverboard, and the "Jaws 19" gag, but somehow, the whole movie lacked the heart of the first. There is something delightful, simple and human about the first film's plot; the second one is larger in scale, and somehow, a sense of urgency and engagement is lost. And it doesn't function on a human level the same way the first one did.

Part III had more heart than II, but it at times felt lazy and uninspired. The series lost some more steam here. When I was younger, I almost never watched this film, but today, I consider it the better sequel. A sweet aspect of the film is Doc's love for 1885's Clara, played by Mary Steenburgen.

Oh, and the car! The DeLorean. It's really something, how this brilliant time travelling car has embedded itself into pop culture, and with good reason. It's not an H. G. Wells-esque time machine; it's damned sportcar! Why? Well, as the Doc says, "If you're gonna build a time machine into a car, why not do it with some style?" It's a good thing that Zemeckis and his team didn't go with their initial idea of making the time machine a refrigerator. I have two model DeLoreans. I suspect I would not have bought two model refrigerators.

My unconditional love for "Back to the Future" led me on a quest to track down other Zemeckis features. We bought the VHS of "Who Framed Roger Rabbit" and sat down to watch it. This was years ago. I was just eight or nine.

One minute into the movie, my father suspected that it was the wrong cassette in the box--he had heard that "Who Framed Roger Rabbit" was a film in which live-action and animated characters co-existed, but what we were watching was simply an animated short. Two to three minutes in, it didn't matter, for it was turning out to be a great animated short anyway. And at around the four minute mark, we were amazed. Just after Roger Rabbit drops the refrigerator on his own head while trying to save Baby Herman, the director of the animated short, who turns out to be 'real live-action', screams "Cut!," steps into the shot, and loudly reproaches Roger for having tweeting birds flying around his head in circles when the script clearly mentions that the "Rabbit gets klunked, rabbit sees stars." Not birds, stars, the director yells at him. Oh, was it startling to see that 'real' director shouting at the animated mammal. And then seeing the toon Baby Herman smoking a cigar and shouting at the director in a voice a tad too mature for someone of his stature, "How many times do we have to do this damn scene?! I'll be in my trailer, taking a nap!"

"Who Framed Roger Rabbit" is incredibly funny and displays top notch craftsmanship and such soaring ambition. When you watch it the first time, you will initially be amazed at the effort and creativity that, obviously, has been so lovingly poured into it... and then you'll just sit back, have a great time, and laugh with it. It rests among my favorite movies of all time, along with Robert Zemeckis's other great movies "Back to the Future" and "Forrest Gump."

Back then, I just enjoyed the special effects of "Roger Rabbit." I was amazed by how the 'real' bed vibrated and the 'real' sheets creased as the 'toon' Rabbit jumped on it. How he interacted with all the stuff around him; books, letters, doors, drawers, chairs, and people. And then I was amazed by the 'real' Detective Valiant's (mis)adventures in Toon Town. I didn't understand how the animated world and the real world had gotten themselves entangled so beautifully, but I beyond loved every second of it. I learned later that it was all painstakingly planned, shot, and then drawn over. Every frame is the work of intricate pre-production and planning, careful shooting, and then top notch animation.

The end result is seamless.

Today, I admire the film for more than just its craftsmanship. The story is ingenious. The invention is endless. And the actors, including Bob Hoskins's Valiant, know what they're doing. Not even once do they overact; they talk to the cartoon characters straight, just like they would anyone else. And they don't look through the cartoon characters, like in the Disney classics of yesteryear; they're looking at them.

There are other films too. I was a huge fan of "Superman: The Movie," starring Christopher Reeve, but not so much its sequels. I've already written about it here.

Oh, and remember those great Disney live-action comedies? "The Love Bug"? "The Absent-Minded Professor"? "Blackbeard's Ghost"? "Mary Poppins"? They were, and still are, favorites. "The Love Bug" and its sequel "Herbie Rides Again" were my favorites then, but today, I hold true that "Mary Poppins" is one of the greatest live-action children's films ever made. Oh, and here's an interesting fact for you: All the Disney live-action comedies I've mentioned above, and so many others, were directed by the same man: Robert Stevenson. I can only wonder why we don't hear the name more often.

Just the other day, I was watching "Who Framed Roger Rabbit" on my laptop when a college mate sat down next to me and peeked into my screen. "Is this 'Space Jam'?" she asked. I was incredibly offended, but quietly answered, "No. It's 'Who Framed Roger Rabbit'."

She just said, "Oh," or something, and added that she really loved "Space Jam" (1996). And then she walked away.

I sat there, thinking about what she was missing out on and what she had got instead. And then I suddenly felt this surge of gratitude towards my parents, specifically my mother, for showering me with all these great films.

And so, what is this huge, meandering article all about? It is a love letter, or a vote of thanks, or something of the sort. To the great movies of my childhood. And their makers.

And so I thank you, Harryhausen, Spielberg, Zemeckis, Stevenson, and I'm thankful for all your great movies. All of you, in some small or big way, have made me what I am. Sure, my parents started the whole thing, making me, and then making me who I am, but you guys helped out along the way.

Thank you.

(P.S. I suppose I've used the words "great," "wonderful," "brilliant" et al too many times, but I don't think I know enough synonyms to compliment these movies and their makers.)