Now streaming on:

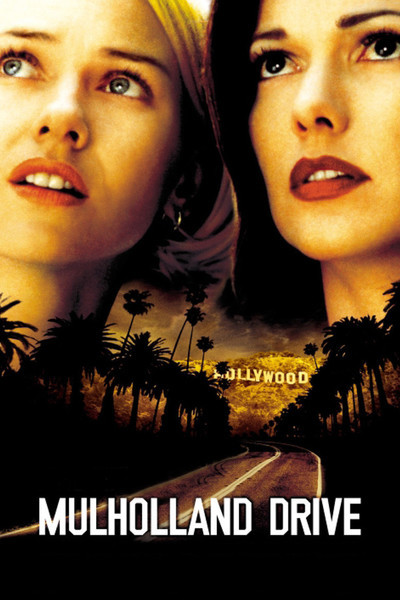

It's well known that David Lynch's "Mulholland Dr." was assembled from the remains of a cancelled TV series, with the addition of some additional footage filmed later. That may be taken by some viewers as a way to explain the film's fractured structure and lack of continuity. I think it's a delusion to imagine a "complete" film lurking somewhere in Lynch's mind — a ghostly Director's Cut that exists only in his original intentions. The film is openly dreamlike, and like most dreams it moves uncertainly down a path with many turnings.

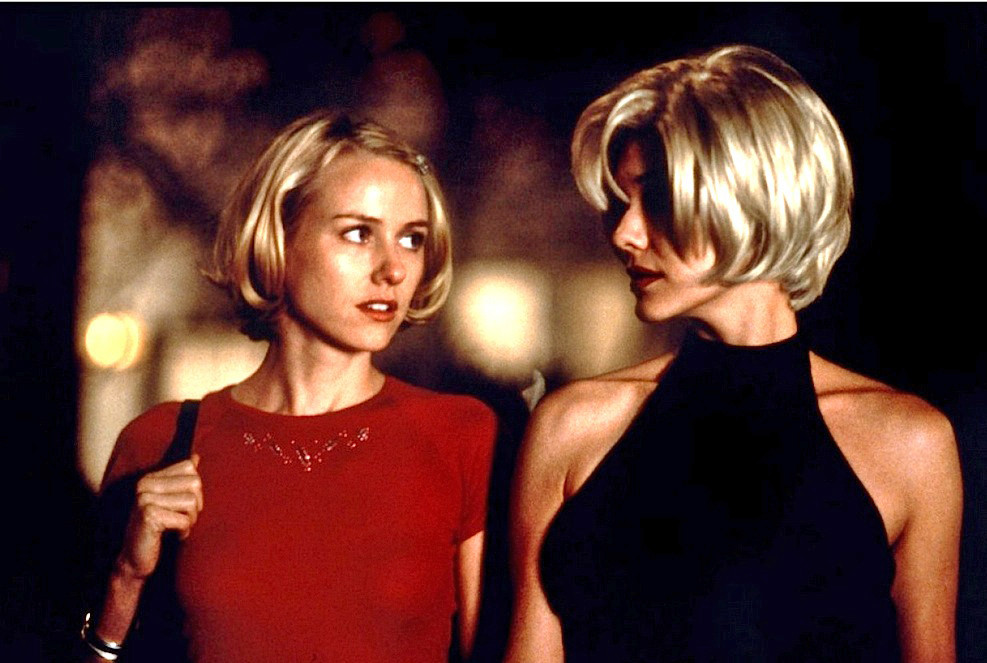

It seems to be the dream of Betty (Naomi Watts), seen in the first shots sprawled on a bed. It continues with the story of how Betty came to Hollywood and how she ended up staying in the apartment of her aunt, but if we are within a dream there is no reason to believe that on a literal level. It's as likely she only dreams of getting off a flight from Ontario to Los Angeles, being wished good luck by the cackling old couple who met her on the plane, and arriving by taxi at the apartment. Dreams cobble their contents from the materials at hand, and although the old folks turn up again at the end of the film their actual existence may be problematic.

The movie seems seductively realistic in several opening scenes however, as an ominous film noir sequence shows a beautiful woman in the back seat of a limousine on Mulholland Drive — that serpentine road that coils along the spine of the hills separating the city from the San Fernando Valley. The limo pulls over, the driver pulls a gun and orders his passenger out of the car, and just then two drag-racing hot rods hurtle into view and one of them strikes the limo, killing the driver and his partner. The stunned woman (Laura Elena Herring) staggers into some shrubbery and starts to climb down the hill — first crossing Franklin Dr., finally arriving at Sunset. Still hiding in shrubbery, she sees a woman leaving an apartment to get into a taxi, and she sneaks into the apartment and hides under a table.

Who is she? Let's not get ahead of her. The very first moments of the film seemed like a bizarre montage from a jitterbug contest on a1950s TV show, and the hotrods and their passengers visually link with that. But people don't dress like jitterbuggers and drag race on Mulholland at the time of the film (the 1990s), not in now-priceless antique hot rods, and the crash seems to have elements imported from an audition, perhaps, that will later be made much of.

I won't further try your patience with more of this mix-and-match. Dreams need not make sense, I am not Freud, and at this point in the film it's working perfectly well as a film noir. They need not make sense, either. Conventional movie cops turn up, investigate, and disappear for the rest of the film. Betty discovers the woman from Mulholland taking a shower in her aunt's apartment and demands to know who she is. The woman sees a poster of Rita Hayworth in "Gilda" on the wall and replies, "Rita." She claims to have amnesia. Betty now responds with almost startling generosity, deciding to help "Rita" discover her identity, and in a smooth segue the two women bond. Indeed, before long they're helping each other sneak into apartment #17. Lynch has shifted gears from a film noir to a much more innocent kind of crime story, a Nancy Drew mystery. When they find the decomposing corpse in #17, however, that's a little more detailed than Nancy Drew's typical discoveries.

What I've been doing is demonstrating the way "Mulholland Dr." affects a lot of viewers. They start rehearsing the plot to themselves, hoping that if they retrace their steps they can determine where they are and how they got there. This movie doesn't work that way. Each step has a way of being like an open elevator door with no elevator inside.

Unsatisfied by my understanding of the film, I took it to an audience that hadn't failed me for 30 years. At the Conference on World Affairs at the University of Colorado at Boulder, I did my annual routine: Showing a title on Monday afternoon, and then sifting through it a scene at a time, sometimes a shot at a time, for the next four afternoons. It drew a full house, and predictably a lot of readings and interpretations. Yet even my old friend who was forever finding everything to be a version of Homer's Odyssey was uncertain this time.

I gave my usual speech about how you can't take an interpretation to a movie. You have to find it there already. No consensus emerged about what we had found. It was a tribute to Lynch that the movie remained compulsively watchable while refusing to yield to interpretation. The most promising direction we tried was to delineate the boundaries of the dreams(s) and the identities of the dreamer(s).

That was an absorbing exercise, but then consider the series of shots in which the film loses focus and then the women's faces begin to merge. I was reminded of Bergman's "Persona," also a film about two women. At a point when one deliberately causes an injury to the other, the film seems to catch on fire in the projector. The screen goes black, and then the film starts again with images from the earliest days of silent film. What is Bergman telling us? Best to start over again? What is Lynch telling us? Best to abandon the illusion that all of this happens to two women, or within two heads?

What about the much-cited lesbian scenes? Dreams? We all have erotic dreams, but they are more likely inspired by desires than experiences, and the people in them may be making unpaid guest appearances. What about the film's material involving auditions? Those could be stock footage in any dream by an actor. The command about which actress to cast? That leads us around to the strange little man in the wheelchair, issuing commands. Would anyone in the film's mainstream have a way of knowing such a figure existed?

And what about the whatever-he-is who lurks behind the diner? He fulfills the underlying purpose of Lynch's most consistent visual strategy in the film. He loves to use slow, sinister sideways tracking shots to gradually peek around corners. There are a lot of those shots in the aunt's apartment. That's also the way we sneak up to peek around the back corner of the diner. When that figure pops into view, the timing is such that you'd swear he knew someone — or the camera — was coming. It's a classic BOO! moment and need not have the slightest relationship to anything else in the film.

David Lynch loves movies, genres, archetypes and obligatory shots. "Mulholland Drive" employs the conventions of film noir in a pure form. One useful definition of noirs is that they're about characters who have committed a crime or a sin, are immersed with guilt, and fear they're getting what they eserve. Another is that they've done nothing wrong, but it nevertheless certainly appears as if they have.

The second describes Hitchcock's favorite plot, the Innocent Man Wrongly Accused. The first describes the central dilemma of "Mulholland Dr." Yet it floats in an uneasy psychic space, never defining who sinned. The film evokes the feeling of noir guilt while never attaching to anything specific. A neat trick. Pure cinema.

This film is streaming on Netflix Instant. Also in my Great Movies Collection: "Persona."

You can comment under my related blog post on the film, here.

Roger Ebert was the film critic of the Chicago Sun-Times from 1967 until his death in 2013. In 1975, he won the Pulitzer Prize for distinguished criticism.

147 minutes