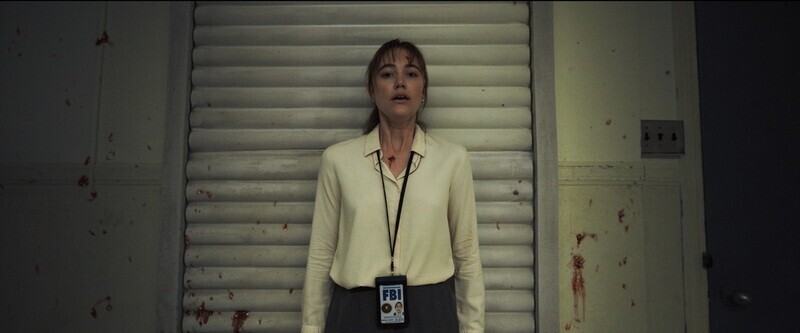

From the very first frame of “Longlegs,” director Osgood Perkins revels in crafting scares through dissonance and contrast. In the opening, we witness a young girl walking outside her where snow has recently fallen. It’s tranquil and beautiful, framed almost as a moving photograph. Nothing about this should feel disturbing and yet just in the framing, Perkins crafts a sense of dread that gnaws. Rather than create a sense of intimate safety through a close-up, he lets the camera stay zoomed out for a while as if to hint that a whole host of unholy horrors could creep into the frame at any moment. Moments like these make “Longlegs” so unnerving, as the safety and comfort that comes with quotidian rhythms and bright open spaces become the very venues for hell to be unleashed.

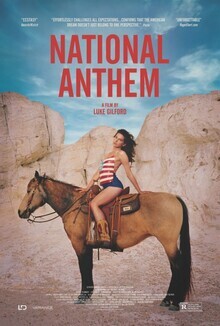

Set in the 1990s but frequently jumping around to different time periods, which further contributes to a sense of disorientation, the film focuses on a newly minted FBI Agent Lee Harker (scream queen Maika Monroe, who manages to make every exhale feel like an exorcism) as she works to stop the titular Satanic serial killer Longlegs (Nicolas Cage, looking like a mid-life crisis Pennywise) from killing again. “Longlegs” spins an ambitious yarn as it comments on everything from the Satanic panic of the late 1900s, haunted artifacts, and the ways religious devotion can easily morph into fatal fanaticism. Yet it’s all reined in by Perkins’ clear vision and focus. As much as he relishes in the scares, he knows the terrors he’s engineered are all in service for the deeper questions he’s exploring.

“If what you’re interested in is the romanticism and the poetry of the unknown, you can't just play that end of the keyboard. You got to play the other notes too,” he shared, “My responsibility is to make something that feels true, even if my film deals with the supernatural, mystical, or fantastical. If it is rooted in a truth, then it holds itself together.”

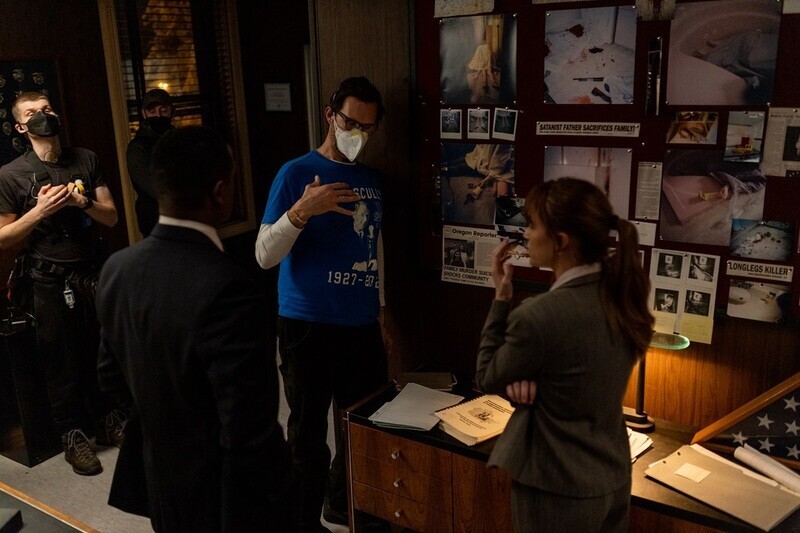

Over Zoom, Perkins spoke with RogerEbert.com and dissected his approach to depicting supernatural forces in a grounded way, how he sought to make prayer terrifying, and how the presence of humor nuances (and emboldens) the scares in the film.

This conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

I know that you had concocted the character of Longlegs for a long time but as you described, he was a character searching for a narrative home. How did the character develop and grow as you grew as a filmmaker?

Osgood Perkins: If you’re in my job, a writer-director who is freelance and who doesn’t have a studio behind them, some fantastic amount of money, or some rich IP … the task is sitting down every day and making stuff up. You keep showing up, practicing, writing words, erasing things etc. If you’re doing that all the time, you’re creating a lot of material that doesn’t have a home when you make it.

Longlegs was this entity that kept surfacing in things that I was trying to write. There would be moments where I’d have written a scene or an act of something, and he was this shadowy figure who was in the fringes of those moments, peeking around and trying to fit into the story. From the start, I knew that he was this weird and uneasy guy who had performance anxiety. I thought he could be a birthday clown or a birthday performer … that kind of person who comes to your house and talks to your kids when he’s not there. Throughout my screenwriting, I wrote various interactions and scenes between him and children.

Throughout the years he’s had different names. He was trying to find his spot. Then when I landed on doing a “The Silence of the Lambs” riff, I knew the film needed a monster, a killer the protagonists couldn’t catch. This guy who had been trying to get into these other movies that I was writing raised his hand and said, “Put me in coach.”

It wasn't the supernatural gothic horror film, nor the Brothers Grimm retelling, but this serial killer procedural, where Longlegs finally got to play.

He was a good fit. Everything is just practice and process. You have to listen to stuff that’s in your environment. Stuff your kids say, people you meet on the street, interactions you have on the subway, park, or coffee shop … I was collecting all these things while creating this character. Listening to music, the stuff I was reading … all of that goes into the cauldron of character creation. It’s just shaping stuff and making sculptures out of clay.

It requires you to pay attention to what’s around you, and it’s neat to think of the Longlegs we see on-screen as a time capsule of sorts of all the influences that have formed you up until that point.

Exactly.

The film's depiction of violence certainly has its brutal moments, but you don’t revel or linger in it; there are these jolting moments of murder before the camera cuts away. I’d love to hear about your decision to practice restraint and how you navigated those moments of where to depict violence and when to cut away.

If you can imply something, it’s always better than showing it. That’s an easy rule.

The dialogue is also incredibly violent … I think of Kiernan Shipka’s one scene-stealing moment, where she rasps out some bone-chilling threats to Maika’s character.

If you can say that a thing is going to happen and then stir that pot and have your characters be anxious about it and have it be looming, the audience will fall in step with that. If you can use a few words to paint a big picture, it works. I cringe over extreme violence … it doesn’t turn me on in any way. So I try to give the audience just enough which turns out to be the right amount for me. At the end of the day, that’s just the director’s job. I have to measure and balance what works for me and make something that’s true to myself and hope that it’s accessible and true for a larger audience too.

That authenticity you’re talking about also courses through some of the film’s key themes. One layer that resonated with me was how you made prayer terrifying. You got at this notion that prayer isn’t just about supplication and asking a higher power for things, but it’s about aligning our hearts and desires to what we’re praying to. The film was a horrifying depiction of what happens when we allow ourselves to be willingly formed by evil and the fallout of when who we pray to doesn’t have our best interests in mind.

I was exploring the effectiveness of ritual and our belief in faith in these things that live outside ourselves. I was questioning one’s investment in these higher powers and wondered whether giving away your presence and power when you’re praying to some outward thing … if that ultimately matters or is effective. I mean, of course, it does matter to some extent. I’m not trying to belittle anyone’s belief or what people adhere to and what’s worked for them. But for me, reaching outside of yourself for some salvation or solution doesn’t necessarily ring true. Ultimately, we’re alone, and we have to do it for ourselves. So with “Longlegs,” I really did want to ask, “Does prayer work?” In the context of this horror movie, I’m supposing that prayer doesn’t really work and that it’s a little bit bleaker out there than it seems.

Alicia Witt, who plays Harker’s mother, repeatedly asks her daughter if she’s said her prayers. In her, we really see what happens when prayer turns malicious, and faith mixes with fanaticism.

Yeah, well, that’s a big problem right there.

I know we’ve spent a lot of time talking about the film’s darkness but I was surprised at how funny this film was. Everything Blair Underwood says in this film cracks me up. What was it like to strike that tonal balance?

It's all on the page. The scripts that I do are very finished. I don’t come with this attitude of “Oh I might rewrite this script later at lunch.” When I get people involved in a project, they get involved in a very finished script. My sensibility is just like that; I tend to joke and might light of things because it seems more intelligent that way. It’s a way to acknowledge that things can be both horrible and funny simultaneously. I think we all know that feeling of “happy sad.” There’s much more curiosity, mystery, and depth around an emotion like “happy sad” than there is around just “happy.”

I try to blend in disparity and other emotions that seem like they don’t go together because it creates a better texture. I’m just trying to make things stand out and have a little relief. By relief, I mean texture … with these emotions, I want you to feel the grooves and bumps, the highs and lows. It’s like music in that there’s a rhythm, melody, and movement. It’s a way for me to make the material dynamic, and I think the best way to do that is to acknowledge that there are two poles to everything, two sides to each coin.

There’s a line that Michelle Choi-Lee’s character says that embodies that: “He worships the devil, that’s for sure. But in the USA, you’re allowed to do that.”

Right? It's a funny line. Everybody laughs at it, but when you dissect it and look at the words, it’s also frightening.

Nicolas Cage has mentioned how the horror genre is liberating because, for all creatives involved, you’re not locked into the material dimensions and can be creative. You’ve already shared how tight and completed your scripts are, but I’m wondering what it’s like to ground some of the otherworldly, spiritual horrors you explore while also wanting to keep grounded in the real world.

That dance between the ethereal and the supernatural, the hidden and the mysterious, and the unknowable and concealed … that is all interesting to me. That’s my focus. The balance then becomes the breadcrumbs, the clues, the crime scene photographs, the cryptic codes, the algorithms … the hard things you can feel, touch, and make a file out of that can counterbalance to the infinite. If you’re interested in the romanticism and poetry of the unknown, you can't just play that end of the keyboard. You have to play the other notes, too, where all of the FBI procedural stuff comes in as I explore these supernatural horror elements. Doing this also orients the audience; they stay connected if they have something they can follow that’s hard-edged like a clue. But for me, the clues and the breadcrumbs are only in service of the abstract.

You shared in an interview when “The Blackcoat’s Daughter” played for the Chicago Critics Film Festival, that that film was about trying to reconcile your inability to know your father. “Longlegs,” to some extent, explores this but about your mother. What is it like to cinematically explore this question of reconciliation when that conversation is one-sided?

Whatever I feel or think will be my own and will be different from how others view the movie. My responsibility is to make something that feels true, even if my film deals with the supernatural, mystical, or fantastical. If it is rooted in a truth, then it holds itself together. If there’s a center, then there’s something it can orbit around. If you don’t have something true you’re working from and you’re writing all this crazy shit, then it will all fly apart.

That’s because it won’t be attached or grounded in anything. So, as I was working through these questions and reconciliation, I just invited my exploration process. How do I feel about my past? What do I feel now? Is it okay for mothers and fathers to make up stories to protect their children or is it a bad thing? Is it a good thing or is it both things? Those questions become the engine or fuel that I need to produce something interesting to me that matters.

On top of it all, I try to coat it right. I try to dust it with as much other stuff as possible so that little kernel of truth, i.e., those questions I’m asking, are insulated and protected. So with “Longlegs,” I’ve made this far-out fucking crazy procedural horror movie that’s just about this question of: “Is it okay for a parent to lie to a child?” That’s the only thing I’m interested in. The rest is pomp and circumstance … It's the spectacle required to deliver the message or at least the question.

Speaking of spectacle, I hope you’re prepared for everyone who will dress as Longlegs this Halloween. Word on the street is that he’s already becoming a queer icon.

(Laughs) I would love for that to be a thing.

Zachary Lee is a freelance film and culture writer based in Chicago.