Now streaming on:

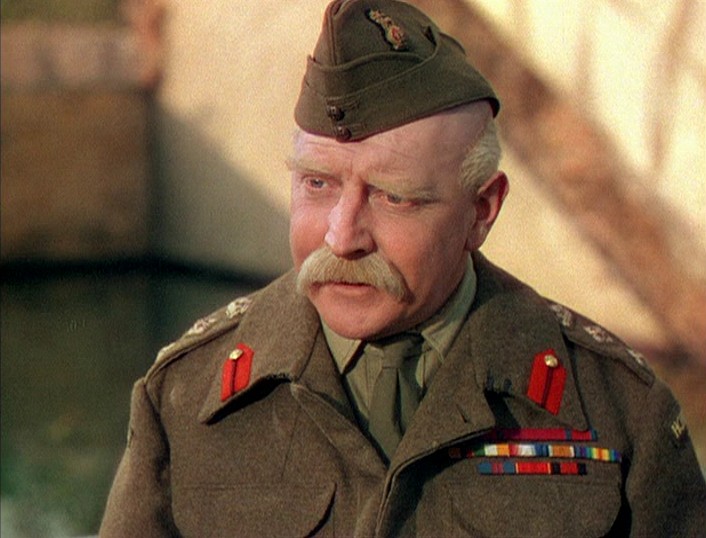

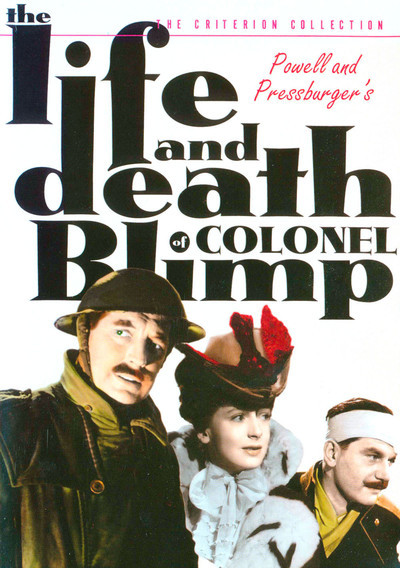

One of the many miracles of "The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp" is the way the movie transforms a blustering, pigheaded caricature into one of the most loved of all movie characters. Colonel Blimp began life in a series of famous British cartoons by David Low, who represented him as an overstuffed blowhard. The movie looks past the fat, bald military man with the walrus moustache, and sees inside, to an idealist and a romantic. To know him is to love him.

Made in 1942 at the height of the Nazi threat to Great Britain, Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger's work is an uncommonly civilized film about war and soldiers--and rarer still, a film that defends the old against the young. Its hero is a blustering old windbag Clive Wynne-Candy, a war-horse of the Army since the Boer War, now twice retired from regular duty and relegated to leading the Home Guard.

As the film opens, the general has ordered military training exercises and announced, "War starts at midnight." A gung-ho young lieutenant decides that modern warfare doesn't play by the rules, and jumps the gun, leading his men into the General's London club and arresting him in the steam room. When Wynne-Candy bellows, "You bloody young fool--war starts at midnight!" the lieutenant observes that the Nazis do not observe gentleman's agreements, and insults the old man's belly and mustache.

Wynne-Candy is outraged. "You laugh at my big belly but you don't know how I got it! You laugh at my mustache but you don't know why I grew it!" He punches the young lieutenant, wrestles him into a swimming pool--and then, in a flashback of grace and wit, the camera pans along the surface of the water until, at the other end, young Clive Candy emerges. He is thin and without a mustache, and it is 1902.

"The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp" has four story threads. It mourns the passing of a time when professional soldiers observed a code of honor. It argues to the young that the old were young once, too, and contain within them all that the young know, and more. It marks the General's lonely romantic passage through life, in which he seeks the double of the first woman he loved. And it records a friendship between a British officer and a German officer, which spans the crucial years from 1902 to 1942.

This is an audacious enough story idea to begin with, but even more daring in 1942, when London was bombed nightly and the Nazis seemed to be winning the war. Powell at first wanted Laurence Olivier to play his title role, but the screenplay ran into fierce opposition from Winston Churchill, and the Ministry of War refused to release Olivier from military duty. Then Powell cast Roger Livesay, a young actor who had worked for him before, and as the German officer, an emigre Austrian actor named Anton Walbrook.

That led to an encounter between Churchill and Walbrook, recounted by the British film critic Derek Malcolm: "Churchill's reaction was furious. He is said to have stormed into Walbrook's dressing room when he was appearing in a West End play demanding: 'What's this film supposed to mean? I suppose you regard it as good propaganda for Britain.' Anton's reply was quite telling, he said 'No people in the world other than the English would have had the courage, in the midst of war, to tell the people such unvarnished truth'."

Ah, but he praised his adopted homeland too soon. Churchill continued to resist. Powell could not borrow gear and trucks from the Army, "so we stole them." The film was at first banned, then reluctantly released in a shorter version, and in the U.S. it lost 50 minutes of its 163-minute running time; the entire flashback structure was replaced by a chronological story line. Only in 1983 was the film finally restored, and hailed as a masterpiece. "It stands," wrote the critic Dave Kehr, "as very possibly the finest film ever made in Britain."

"The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp" is a film of balance and insight--a civilized film, which even in a time of war celebrates civilized values. What it regrets is the loss, in two World Wars, of a sense of decency and fair play that had governed the European military classes. Near the film's end, the German refugee corrects the sentimentalism of the old general, telling him from first-hand experience that Nazism is the greatest evil the world has ever known, and saying there is no point in playing fair when the enemy plays foul, if that means you lose, and evil wins.

Despite this sober undercurrent, "Colonel Blimp" is above all a comedy of manners, and Powell and his writing and producing partner Pressburger conduct it with style and humor. Jolly music underlines an opening sequence in which motorcycle messengers distribute news of the war games, and there is wit in the movie's ingenious flashbacks and flash-forwards. Photographed by Georges Perinal with help from Jack Cardiff, the movie is one of the best-looking Technicolor productions ever made, its palate controlled to make wise use of bright contrasts in a world of subdued harmony.

Several scenes surprise us by how they pay off. Note the early duel between the British and German officers (they do not even know one another; the German was drawn by lot to respond to an insult to the German army). A high-angle shot refuses to take sides, the Swedish referee scuttles back and forth like a crab--and then, just when we expect to see the outcome, the camera cranes up to an exterior shot of the Army gymnasium (a model), with snow falling on Berlin. The message is made visually: The season of traditional values is ending, and these soldiers will not again play so fair.

In hospital, Clive Candy and his opponent, Theo Kretschmar-Schuldorff, are visited by Candy's British friend, Edith Hunter (Deborah Kerr). The German falls in love with her and proposes marriage. Candy is at first delighted, but as he returns home he realizes he loved her, too, and begins a lifelong search for a substitute. Fifteen years later, in a World War One hospital, he sees a young nurse who is Edith's spitting image, and arranges a dance for war nurses just to meet her again. This is Barbara Wynne, again played by Deborah Kerr. Note the dinner scene when Candy explains his motive for seeking her out, and the subtle chill with which Barbara says she quite understands. The marriage fades out like the duel did, as if there is nothing else worth saying.

Kerr appears a third time as a working-class girl named Angela Cannon, who is Wynne-Candy's driver during the Second World War. It is a remarkable performance by the 20-year-old newcomer, playing three roles; Wendy Hiller was originally cast, but became pregnant, and Powell cast Kerr both because he thought "she would be a star one day," and because he was falling in love with her.

The friendship between Clive and Theo is traced for 40 years. They meet again at a German prisoner's camp in England, after World War One; Theo ignores Clive and stalks away, but the next day calls to apologize, and is a guest at a dinner of British establishment types at which, gentlemen all, they assure him his homeland will be rebuilt: "Europe needs a healthy Germany!" When the two men meet again, it is after the German has fled his homeland in 1939. In a long speech all done in one take, the explains why he has chosen England over his birthplace. Walbrook's acting here is sublime with its mastery of tone and mood, and this speech, more than any other, explains why Churchill was wrong to oppose the film.

The most poignant passages involve the general growing older. He looks like a caricature to younger officers--with his beefy face, pink complexion, mustache (grown to hide the dueling scar) and raspy voice. But in his heart he is still young, still in love, still idealistic. At the end of the movie he looks at a water pool in the basement of his bombed-out house, and is reminded of a lake across which he once pledged love. And he insists to himself that it is the same lake, and he is the same man. Rarely does a film give us such a nuanced view of the whole span of a man's life. Is is said that the child is father to the man. "Colonel Blimp" makes poetry out of what the old know but the young do not guess: The man contains both the father, and the child.

Roger Ebert was the film critic of the Chicago Sun-Times from 1967 until his death in 2013. In 1975, he won the Pulitzer Prize for distinguished criticism.

163 minutes