Now streaming on:

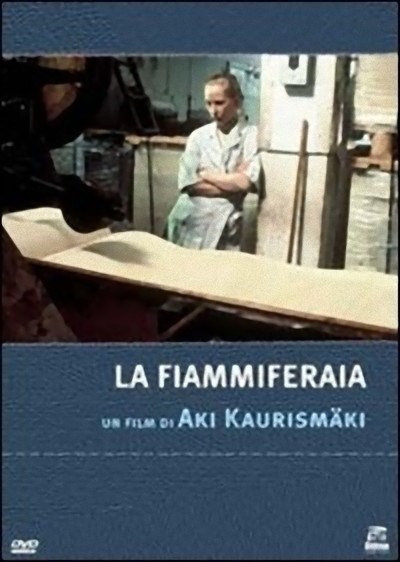

This poor girl. I wanted to reach out my arms and hug her. That was during the first half of "The Match Factory Girl." Then my sympathy began to wane. By the end of the film, I think it's safe to say Iris gives as good as she gets.

The film begins with a big log. In documentary style, we see what happens to it. It has its bark stripped off. Blades shave thin sheets from it. These sheets are chopped into matchsticks and divided and stacked and dipped and arrayed and portioned into boxes, which are labeled, packed into larger boxes, and labeled again. That's where Iris comes in. At first we see only her hands, straightening labels, sticking them down, removing duplicates. Then we see her face, which reflects absolutely no emotion.

The Finnish director Aki Kaurismäki fascinates me. I am never sure if he intends us to laugh or cry with his characters--both, I suppose. He often portrays unremarkable lives of unrelenting grimness, sadness, desolation. When his characters are not tragic, he elevates them to such levels as stupidity, cluelessness, self-delusion or mental illness. Iris, the match factory girl, incorporates all of these attributes.

She is played by the actress Kati Outinen, a Kaurismäki favorite who has often starred for him. Whatever it is she does, she is very good at it. His camera stares at her, and she stares back. She is a pale blonde, slender, with a receding chin and eyes set deep in pools of mascara. If she were to laugh, that would be as novel as when Garbo talked for the first time. It would be easy to describe her as "plain," but you know, she would have a pretty face if she ever animated it with a personality. In "The Match Factory Girl" she is deadpan and passive, a person who is accustomed to misery.

Her job at the match factory is boring and thankless. She is one of the few humans among the machines. She takes the tram home to Factory Lane, where a shabby alley door admits her to the two-room apartment she shares with her mother and stepfather. They sit in a stupor watching the news on TV. Her mother smokes mechanically, so listless long ashes gather on her cigarette. Iris cooks dinner, serves it, and sits down with them. A soup has pieces of meat in it, and her mother reaches out a fork and stabs a bite from Iris' plate. She is expected to do all the cleaning, sleep on the sofa, and pay rent.

In the evenings she goes out seeking companionship, and is ignored. At a club, nobody asks her to dance. In a bar, she locks eyes with a bearded man. His gaze is aggressive, not affectionate. They sleep with one another. He never calls her again. She goes to his flat to indicate she cares for him. He tells her, “Nothing could touch me less than your affection.” That's all he ever says to her. Her stepfather says less. "Whore," he calls her, after she spends some of her paycheck on a pretty red frock.

I watched hypnotically. Few films are ever this unremittingly unyielding. I found myself as tightly gripped as with a good thriller. I could hardly believe the litany of horrors. What made it more mesmerizing is that it's all on the same tonal level: Iris passively endures a series of humiliations, cruelties and dismissals. This cannot be tragedy because she lacks the stature to be a heroine. It cannot be comedy because she doesn't get the joke. What can it be?

Kaurismäki has made many films with hapless characters. When I say that when I see each one it makes me eager for the next. I suppose my description makes this one sound depressing, but although it is about a depressed woman it is always challenging us, nudging, teasing our incredulity. When Kaurismäki has an entry in a film festival, I will make it my business to see it.

I've reviewed four of his other films: "Ariel" ("the character's lack of physical and social finesse is a positive quality") ; "Lights in the Dusk" ("his characters are dour, speak little, expect the worst, smoke too much, are ill-treated by life, are passive in the face of tragedy.") ; "Drifting Clouds" ("he wants his characters to always seem a little too large for their rooms and furniture") ; and "The Man Without a Past" ("He finds a community of people who live in shipping containers. There is a kind of landlord, who agrees to rent him one").

Not all of these films are as dour as "The Match Factory Girl." Some of his characters are more resilient. I never get the idea he hates them; in fact, I think he loves them, and feels they deserve to be seen in his movies, because they are invisible to other directors. In making them, he seems to be consciously resisting all the patterns and expectations we have learned from other movies. He makes no conventional attempt to "entertain." That's why he's so entertaining. He wants only to hold our interest. He wants us to decide why he chooses such misfits, loners and outsiders, and to ask how they endure their lives. Even those who are not victims have a passive acceptance bordering on masochism. Life has dealt them a losing hand, and that's how it is.

Kaurismäki's camera work is meticulous. He composes without any eagerness to put elements in or leave elements out; his camera simply votes "present," and gazes with the same dispassionate eyes that Iris has. An image is there before us. We see it. There you have it. We can draw our own conclusions. He doesn't go in for reaction shots, or perhaps it would be more fair to say that every shot is a reaction shot. Asked at a film festival why he moves his camera so little, he explained: "That's a nuisance when you have a hangover."

He is often compared to Robert Bresson, who also made films about isolated, lonely characters ("Mouchette," about a village outcast; "Diary of a Country Priest" about a disliked and unsuccessful young priest; "Au Hasard Balthazar" about a mistreated donkey). Both directors use an objective gaze. Both move deliberately. (Told he must have been influenced by Bresson, Kaurismäki said, "I want to make him seem like a director of epic action pictures.”) Actually few directors are more different. Bresson's films are deeply empathetic, spiritual, transcendental. Kaurismäki seems detached from his characters. Most of his films could open with the title card, "Here's another sad sack."

But there's something concealed beneath the attitude of detachment. He invites us to peer closely at these people he pins so precisely to the screen. What does it say that there can be such lives? How do people endure it? How do some of his characters even prevail? In "Drifting Clouds" again starring Kati Outinen as a luckless waitress with a jinxed husband, there is actually dark humor in the way the clouds are always dark and rainy. As sad as her life is, the film is immensely amusing in its over the top bad luck. When her luck changes at the end, it's thanks to the Helsinki Workers' Wrestlers Association.

Growing up in Finland Kaurismäki would certainly have heard Hans Christian Andersen's story "The Little Match Girl." It told the story of a waif in the cold on Christmas Eve, trying to sell matches so her father will not punish her. To keep warm she lights one match after another, and they summon visions which give her comfort. She finally finds happiness of a heartbreaking sort.

In the early scenes of this film Iris doesn't smoke at all. When she finally lights a cigarette--with a match from her factory--it summons visions for her; ideas of revenge. We watch as she acts on these notions. Does she find happiness? That would be asking too much. But she finds… satisfaction.

"The Match Factory Girl" is the third film in Kaurismaki's Proletariat Trilogy. It follows "Shadows in Paradise," about a aimless garbage collector and "Ariel" (1988), about a coal miner who escapes his subterranean work by turning to crime. The three films have been packaged together and released by Criterion.

Roger Ebert was the film critic of the Chicago Sun-Times from 1967 until his death in 2013. In 1975, he won the Pulitzer Prize for distinguished criticism.

66 minutes