Now streaming on:

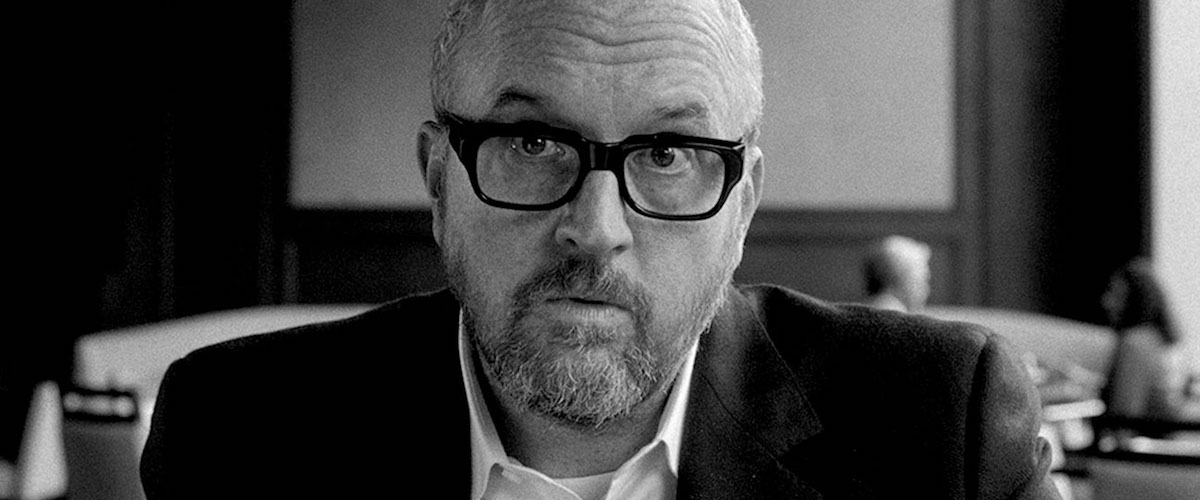

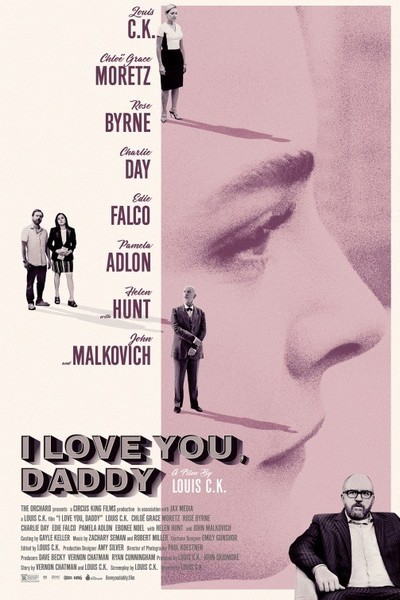

By the time you read this review, Louis C.K.'s semi-satirical showbiz comedy "I Love You, Daddy" will have been consigned to the same pop culture memory hole that contains Jerry Lewis' concentration camp drama "The Day the Clown Cried." The official release date was November 17, 2017. Orchard Films pulled it from the release schedule this morning, November 10, 2017, a day after the New York Times published a story confirming previously unsourced rumors that, over the course of many years, C.K. had exposed himself to women. It's as bad as you've heard. It was that bad even before the news broke. But the news makes the experience of seeing it, and thinking about it, even more unsettling.

The allegations had been bubbling for years under the surface of the mainstream media, which isn't fond of getting sued for libel. C.K. became a critical darling for his FX series "Louie," a groundbreaking quasi-autobiographical comedy-drama. Many critics, myself included, decided—foolishly, in retrospect—to withhold judgment of his guilt or innocence of the allegations and treat the show's scenarios as dramatic abstractions, like anything else you'd see on a TV series or in a movie. When you see this film—as some of you will, out of grim curiosity or historic interest—you might be as appalled as I was when I saw it a couple of weeks before its distributor pulled it from release and realized he'd been playing the entire world for a bunch of suckers.

If there's one thing we know for sure about people who are accused of indecent exposure, it's that the thrill of getting away with it is the true source of their power. In retrospect, much of "Louie" now plays like a dry run for what he'd do on the big screen with "I Love You, Daddy.” The show exposes its true self deftly enough that you aren't sure you saw what you saw. This film leaves the raincoat open while its owner makes eye contact and dares you to deny what's happening. My notes consist of a single sentence: "It's like he's rubbing it in our faces."

It seems astonishingly brazen, under the circumstances, that of all the stories C.K. could have chosen to tell, he chose this one. "I Love You, Daddy" is about a Louis C.K.-like TV auteur, played by Louis C.K., who has an affair with the star of one of his TV shows (Rose Byrne), a woman he cast partly because he was sexually attracted to her. At the same time, his daughter (Chloe Grace Moretz), a minor who just turned 17, is starting an affair with a sixty-something film director (John Malkovich) who is legendary for his skill and productivity but also notorious for making films about older men having affairs with much younger women and doing the same thing in real life. The film director is modeled, of course, on Woody Allen, one of C.K.'s heroes, a great American filmmaker who has also been accused of child molestation and who, point of fact, married his ex-girlfriend Mia Farrow's daughter, a few years after they began an affair under Farrow’s roof. (She was 19, he was about 50.)

The mere fact of this film's existence sounds like the plot of a never-made episode of "Columbo," the great TV series starring Peter Falk as a rumpled, working class detective. Columbo usually investigated murders by rich, powerful men so arrogant that they failed to realize that their guilt was obvious to Columbo. The detective's favorite strategy was to flatter the arrogant rich guys into talking about how brilliant and accomplished and amazing they were, until they either let a damning detail slip or brazenly taunted Columbo with the painfully obvious fact that they did it. In a hypothetical "Columbo" episode about sex crimes, "I Love You, Daddy" would be the document that slapped the cuffs on Louis C.K.

For starters, this is a film that declares spiritual kinship between C.K. and Allen‚ a director whose best work is often much more (horrifyingly) honest about amorality than C.K. is here—maybe not what you'd call a great compliment to Allen, but whatever else you can say about him as a person or a film director, you can't say he's never warned us against sentimentalizing him. Consider "Husbands and Wives" and "Manhattan," among other film starring Allen as a forty- or fifty-something man who can't keep his hands off a teenager or twenty-something, and who either come to their senses at the last minute ("Husbands and Wives") or spiral into sentimental delusions that the movie is happy to validate ("Manhattan"). Then consider "Crimes and Misdemeanors" and "Match Point," both of which hinge on the questionable assertion that any one of us is capable of the absolute worst behavior once we realize morality is merely a human construct and God isn't watching us. (Quite a bit of projection on Allen's part when you think about it.) The black and white photography, New York setting and lush orchestral score of "I Love You, Daddy" all evoke "Manhattan," the go-to film that Allen's detractors point to whenever they insist that he has to be guilty of the worst things a person could possibly say about him.

The relationship between C.K.'s producer and Byrne's leading lady is suffused in rationalization: it's a casting couch-style arrangement in which each party blandly exploits the other: she turns on the charm and flattery the second she walks into his office and he invites and revels in it, as if to say, "This is how things get cast, it's no big deal, everybody does it." The relationship between the director and the hero's daughter is likewise normalized; C.K. wrings anxious humor from the hero's discomfort, but the movie ultimately swings around to the idea that at 17, she's an adult who can make her own choices. The hero's daughter makes her entrance in a string bikini, and halfway through there's a scene where she goes bikini-shopping. The warmhearted father-daughter reconciliation near the end is so oblivious to the moral and ethical issues raised by the rest of the film, and so ignorant of how actual fathers and daughters talk to each other, that it manages to out-sick everything else that C.K. has shown us. This is not a film about individuals who have lost their moral compass, but a movie that lacks one, by a director who also lacks one but for many years did a convincing impression of a man who never lost sight of true north.

The lushness of the film's setting—a world of star-studded, flashbulb-dotted premieres, parties in townhouses and mansions, midnight rides in helicopters and the like—recalls Allen's "Stardust Memories," maybe his most withering expression of contempt for his industry, his fans, the women in his life, and himself. The movie's unblinking eye, combined with the lush music, strand the picture in a No Man's Land between sentimentality and satire. It's the place where "edgy" comedies like this settle when they want to simultaneously disturb viewers and make them wonder if there's really something wrong or if they're just misreading signals or assuming the worst. Watching the movie is like being in a situation where you worry that somebody's manipulating you but you can't be certain if you're right. The little voice in the pit of your stomach tells you that something is wrong here, but when you start to articulate objections, the person who's gotten you worried says, "Oh, no! That's not what I meant. Everything's fine. Have a drink! Here, I'll make it for you." Then he turns his back so you can't see what he's putting in the glass.

The half-star is for the cinematography and music. Nice raincoat.

Matt Zoller Seitz is the Editor at Large of RogerEbert.com, TV critic for New York Magazine and Vulture.com, and a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in criticism.

123 minutes

Louis C.K. as Glen Topher

Chloë Grace Moretz as China Topher

John Malkovich as Leslie Goodwin

Rose Byrne as Grace Cullen

Charlie Day as Ralph

Helen Hunt as Aura

Pamela Adlon as Maggie

Edie Falco as Paula